Once Upon a Time

By Rebecca L. Adcock

Introduction

I have a lot of

“once upon a time” stories I could tell (just ask my sons) but the one I want

to tell here is all about mathematics. Of course, it starts out…

Once upon a time I

graduated from the University of Georgia with a Bachelor of Arts degree in

mathematics and computer science. I figured with that kind of degree I would

work at some kind of research facility that needed a person with math knowledge

to code programs analyzing data gathered from experiments, et cetera. Guess

what? Those jobs were scarce but there were numerous jobs in businesses for

people with those same skills. I was hired fresh out of college by an upstart

automobile insurance company. When I was hired, Atlanta Casualty Company had

approximately 65 employees and wrote insurance in one state (Georgia) and when

I left the company had grown to over a thousand employees and was licensed in

over twenty states. I started as the company’s first full-time programmer and

when I left I was a manager in the M.I.S. department.

In the mid 1990’s,

Atlanta Casualty was one of Gwinnett county’s top employers. For most of my

tenure with the company, we were located in the Myrick Building, later called

the DAV Building, and now called Jefferson Plaza, at the intersection of

Peachtree Industrial Boulevard and Holcomb Bridge Road in Norcross. How ironic

that the intersection was named one of the worst intersections in Gwinnett

County because of the number and severity of automobile accidents occurring

there. I remember standing in the Accounting Department on the fourth floor and

watching emergency personnel work a fatal crash. It was a real-life lesson of

why we did what we did. Anyway, Atlanta Casualty is now part of Infinity

Insurance and the offices have moved to the Alpharetta area.

What Is Insurance?

When I first started

working at Atlanta Casualty, I knew as little about automobile insurance as

most twenty-somethings. I knew I paid premiums twice a year and it seemed like

I got nothing in return. Between my new employment and a wreck I had shortly

after I started working, I learned real fast what insurance was all about.

An insurance policy

is a legal binding contract between an individual and an insurance company. In

some cases an agent acts as an intermediary between the individual and the

company. An independent agent can sell insurance policies from any number of

companies and a reputable agent will use his expertise to match his customer to

the company that best suits him, based on a number of factors, including

driving record, driver’s age, vehicle horsepower, and cost of the car when new.

Younger drivers cost more to insure than experienced drivers, and sports cars

more than station wagons. Previous traffic violations tack points onto the

driver’s statistics and each point costs more in premium. A minor infraction

would add one point and a moving violation like speeding could add 3 points.

The money the

customer pays for the insurance, the premiums, goes into an account controlled

and administered by the insurance company. When a customer (the ‘insured’)

suffers a loss, the company (the ‘insurer’) compensates the insured based on

the coverage described in the policy. In the state of Georgia, liability

insurance is required by law. Liability coverage protects the victim in an

automobile accident, the party who was not ‘at fault’. An insured may also buy

physical damage coverage, which would cover his own vehicle even if he is at

fault.

What most people don’t know about automobile insurance

companies is that most of the money collected as premiums is paid back to cover

losses. A typical loss ratio could

run more than 94 cents on the dollar.

To create a profit, an insurance company has to put together a team of

savvy employees, ranging from investment brokers to experienced actuaries. An

actuary analyzes the company’s history of losses and decides who costs the most

to insure. Typically younger drivers suffer from the most accidents and

therefore cause the company to pay out more money. Consequently, the younger

drivers would pay higher premiums for coverage.

Mathematics in an Insurance Company?

Maintenance-Free and

Accurate Code

I was hired as a

programmer at a time when Atlanta Casualty was creating all their own software

applications in-house. I learned pretty fast that knowing some math really paid

off when I was writing code. In

the world of programmers, there are two kinds of tasks. The fun stuff is

creating new programs and systems. The crummy job is maintaining code, yours

and others’. The best way to keep maintenance to a minimum, so you don’t get

stuck maintaining it, is to write efficient code. Given a choice between

storing data that has to be updated infrequently in a table or creating an

algorithm to produce the data, you are better off to create an algorithm that

doesn’t need updating. That way you don’t risk forgetting to maintain the table

and end up sending out checks to customers who didn’t warrant a return premium.

Two problems with that scenario… the bosses aren’t happy…and … try getting that

money back from the customer! If the data is volatile, like insurance premiums

which can be altered twice a year, the programmer can choose to use tables so

code doesn’t have to be changed and retested frequently.

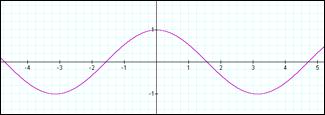

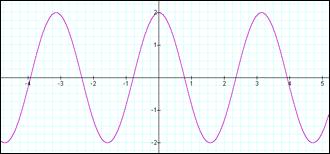

y=cos x

y=2cos 2x

Let me digress for a

moment and mention the similarity between testing a code change and changing a

mathematical equation. If you are teaching the function y=cos x to a class and

you change the function to y=2cos 2x, the students can’t tell which ‘2’ caused

which change in the graph. Did the ‘2’ in front of ‘cos’ cause the height of

the curve to change or did it cause the curve to repeat more frequently over

the same interval? Programming and testing code is similar. I learned to change

one parameter at a time and test it before making another change. It may take a

little longer but the result is consistent, accurate code.

Designing a Database

Besides creating

custom code, programmers at Atlanta Casualty also designed and built their own

database, including the data retrieval system. Prior to creating the database,

we researched what data needed to be captured, the size of each field, whether

the field was alpha or numeric. For instance, we reserved 15 characters to

store the driver license number. At the time, most states had a driver license

number based on the 9-digit social security number. The most glaring exception

was New York, which had a license number of approximately 20 characters. We

were assured by the Vice-President of Product Development that we would write

insurance in New York over his dead body so we set the field at 15 characters.

Numeric fields could be stored as ‘packed’, or ‘double-density’, to save

space. We were working on a

mainframe and data storage was more expensive and fields were fixed, not

delimited by special characters, so field sizes and storage techniques were

important to the overall cost of the project and to the budget of a small and

growing company. We only stored what could not be recreated from other data. It

was considered a waste of space to store anything that could be derived from

other fields.

Another

consideration was the size of each record. Just as data fields were

fixed in size, so were data records

fixed in size. For disk storage efficiency, a collection of records needed to

end at the end of a word boundary.

The Burroughs (and later Unisys) systems we worked on were based on an 8-byte

word and the disk was allocated on a multiple of 8 and 180. If the records were

not evenly divisible then segments of the disk would be wasted.

For a brief tour of

disk storage, follow this link. To get back to this page, use the browser’s

back arrow. http://www.computermuseum.li/Testpage/Disks-Compared.htm

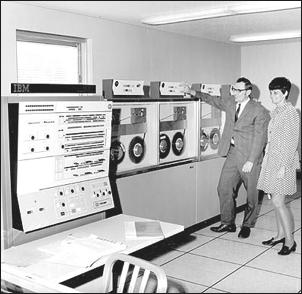

The picture above (on right)

predates my M.I.S. experience (not by much, though).

Probability vs. Evidential

Data

When we think of auto insurance, we may wonder about

our probability of being in a crash. Auto insurance companies don’t deal with

the mathematical intricacies of the probability of an accident occurring to a

particular person in a certain car at a specific location or date. The

actuaries scrutinize the data the company has collected over a period of time

to determine how much money has been paid out for each premium dollar collected

for a particular driver or vehicle. They will look at the following:

Š

the driver’s age.

Š

the territory. This is

where the insured lives or garages the car. Metropolitan areas have higher

premiums than rural areas.

Š

the points on the

drivers’ record.

Š

the symbol and age of

vehicle. Symbol is based on classification of the car as luxury, sports car,

etc. Industry data on the cost to repair the vehicle is also considered in

determining the symbol assigned to a model.

If the company has paid out $1.07 in

losses for each $1.00 collected in premiums for a particular class of drivers,

the actuary may increase the premiums for the class. This can do two things

– the increased premiums will cover the losses or that class of insured

may place their business elsewhere. The actuary walks a tightrope between

keeping the company in the black by collecting enough premiums to cover losses

and trying to keep the premiums competitive with other companies.

Flowchart of part of the actuarial system.

Data Integrity

Based on what you

just read in the previous section, you can see that the integrity of data is

very important to an insurance company. What we found out as we collected this

data was that the accuracy of our data seemed to deteriorate as our data bank

grew. We had more programmers on staff so there were more ‘cooks in the

kitchen’. We were collecting more data than we ever had before. We needed to

establish better controls on all of our data. We had always had balancing procedures

and standards for the billing and accounting systems so now we established

balancing standards on all systems that fed data into the actuarial database.

We knew from experience that we would never be able to balance the premiums to

the penny. We had data coming from multiple systems and rounding discrepancies

and minor errors were a fact of life. We needed to know that we had not

committed operational errors while collecting the data or programming errors

while maintaining code and senior management needed reassurance that we knew

what we were doing. We established a margin of error that was acceptable to us

and to senior management. Now we could balance the system to our controls; if

our results were within our accepted margin, we released the results to the

actuarial department. If we exceeded the acceptable margin, we returned the

system to the programmers and operators.

The End of the Story

I

eventually left Atlanta Casualty company and went to work for a company called

EMS Technologies, also in the Norcross area. I left there to open a retail

franchise with my husband and when he passed away, I returned to my first love

– the desire to teach math. I enrolled in the Master’s degree math

education program at the University of Georgia in August, 2004. In April, 2006,

I accepted a teaching position in a Gwinnett County high school and I look

forward to starting my new career in August.

As I look

back over my previous professional lives, I see that mathematics always played

a significant role. When Bill and I were running our little business, we used

math everyday, calculating customer discounts, balancing the store’s accounts,

ordering product… But wait… that’s a whole other ‘once upon a time…’.